Volatility and credit spreads are two investment arenas where I feel very comfortable making investment bets. The reason that they are easier to predict is that they are mean reverting investment classes. Volatility and credit spreads often spike due to large dislocations in the markets, but they always tend to trend back to a “long-term mean”. This is not to say that long-term means do not change, but just that extremely wide credit spreads or extremely high volatility are fleeting in nature.

Investors in the fixed income world talk about credit spreads via the OAS or option-adjusted spread. This OAS measure basically tells the investor how much more the non-treasury bond is paying over an equal maturity treasury bond. So if we see an OAS of 200 basis points (bps) then we are saying that the bond pays 2% more per year than a comparable treasury bond. The credit spread can be thought of as the premium received for investing in a risky asset. If you invest in a treasury there is nearly a 100% chance that you will get paid back (though it’s getting lower every day). When you invest in a corporate bond such as General Electric, there is a probability that the company will stop making payments or go bankrupt. This risk represents the “default probability” of the bond.

Default levels are tricky to forecast from year to year because they generally happen at high levels during times of distress and then relax back to very low levels. As actual defaults start to spike, then the credit spreads on bonds widen out quickly. The general fact is that credit spreads gap out in reflection of default probabilities that are unrealistic.

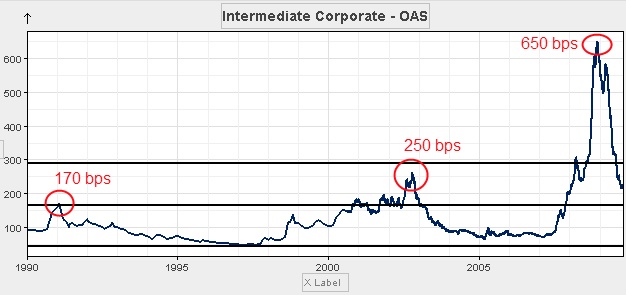

The above chart represents the intermediate duration investment grade corporate credit spreads from the Barclays Aggregate investment grade universe. As you can see, the 650 bps or 6.5% spread between corporate credit and treasuries was multiple levels higher than during the savings and loan crisis of the early 90’s or during the last Minsky credit cycle in the early 2000’s. In the credit derivative world we look at bonds with two things in mind: 1) credit default probability and 2) recovery value. How likely is a bond to default within the time period that I am interested in holding it and how much money will I get back if they do default. If you believed in a 650 bps credit spread and also believed that on average companies that defaulted would recover 40% of their value (used to be the historic average) then you are saying that 43% of the investment grade universe would default over 5 years. On a shorter horizon of 1 year, that same 650 bps translates into over 12% defaulting. According to Moody’s, the highest actual observed default rate for investment grade bonds in 1 year was 1.579% and that was in 1938.

So what drove the extremes of last year? The usual factors – fear, liquidity, uncertainty etc. At a current spread level of about 200bps, high grade credit still looks attractive because that implies a 4% one year default probability if we assume a 40% recovery. Even at a 20% recovery you would still expect 3% defaults which would be an outlier for investment grade default levels.

Take advantage of high investment grade corporate credit spreads (LQD) to add income to your portfolio. Just be careful to protect yourself against rising interest rates because adding a lot of fixed income exposure will hurt you in the long run if interest rates spike and inflation creeps into the economy. A nation full of debt should not be paying 4% on 30 year treasury securities. Look to short treasury futures or the long treasury ETF (TLT).

If you are confused about calculations or default probabilities above, feel free to read the Credit Default Swap primer that I prepared years ago. [Download not found]

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to updates for free: