Many investors are truly afraid of the bursting bond bubble. I have been questioned repeatedly about how worried I am about fixed income returns and rapidly rising interest rates. I generally respond that I do not see any indication of significantly higher interest rates in the near future due to high liquidity (demand for fixed income assets) and lower global growth/inflation. That being said, it is worth taking a bit of time to look at what has historically been a bad bond day.

The general thought process is:

“Bonds have been in a bull market rally since the early 80’s with a steady decline in interest rates. Now we are at very low starting interest rates with nowhere to go but up! Imagine if rates go from 3% on the 10 year to 10% in a short amount of time!”

I appreciate the fear, but here is another thought process. Interest rates have remained low for 5 years. Low cost debt has been “cheap” for companies and qualified investors during that time period. Why does inflation remain stable even though all of this cheap money is available? Maybe the deleveraging cycle can take decades to right itself much as it did following World War II?

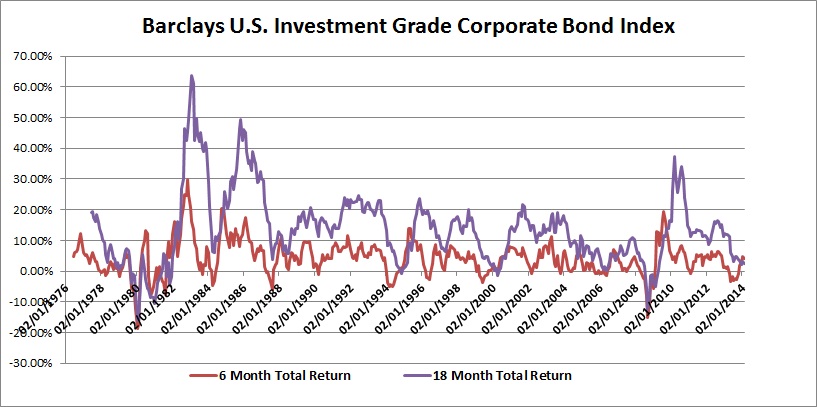

From the return side, let’s look at the bad days. If you look at the rolling total returns of the Investment Grade Corporate Bond Index since 1976, the bad 6 and 12 month total returns were shy of -20% in the early 80’s:

Funny that the upward spiking interest rates of the early 80’s created about the same negative returns of the credit spread blowout in 2008

The funny thing about bonds is that their returns are “self-fixing”. The bonds move back to Par ($100 per face) price at maturity over time. In addition, the investor continues to re-invest his/her coupons at higher interest rates thereby dampening the changes in price of the underlying bond holdings.

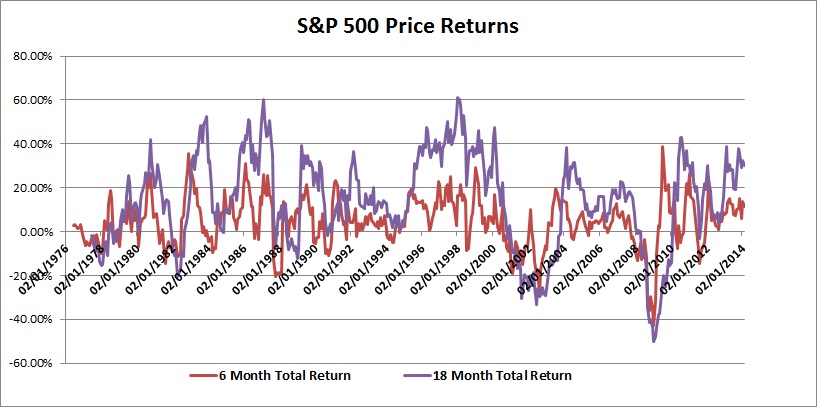

As a comparison we can look at S&P 500 price returns over the same time period. Total returns are not available back to 1976, but they would be very close to the rolling price returns:

Stocks fix themselves as well, but the drawdowns are more frequent and returns are obviously more volatile

As a last point, I think it is worth looking at some fear that we have talked about with regards to the Eurozone countries in 2010-2012 (the P.I.I.G.S). Spain was definitely in the spotlight of potential default with a banking crisis as the tipping point. If we look at the yield of 10 year spanish debt, it got to about 7.5%:

If you look at the short period of time it took to go from 4% to 7.5%, you would expect heavy losses for a nearly doubling of yield

In reality the total return investor in those Spanish 10 year Govie bonds didn’t weather that much pain:

The scary part of these charts is how much that investor has gained since 2012 and how low Spanish yields have gone. We are now at a Spanish 10 year yield of 3.06% and a US 10 year yield of 2.71%. I think I would rather buy a US Bond than a Spanish bond. This brings me to my final point – worrying about quickly increasing US interest rates ignores all of the other countries with bigger problems. Japan and many of the Eurozone countries are further up on the list of collapse probabilities than the United States.

We probably should not force ourselves to buy bonds at the abysmally low current yields, but at the same time we should probably be looking for the risk flare up to occur in a different asset class or geographic location.