This is the third and concluding article in a series that covers the perverse government bailout of AIG. The first piece covered how the insurance industry operates and where problems can arise, the second dove into the moral hazard of the AIG bailout, and this third piece will address not only the risks, but the history of over-the-counter (OTC) trading and what should be done to resolve its weaknesses. I do not believe that OTC trading should go away entirely. OTC trading has served a purpose for specialized transactions or when specific financial instruments are first traded.

When discussing over-the-counter instruments we are not talking about stocks trading via pink sheets or OTC because their price has dropped below exchange listing criteria. We are addressing OTC derivatives such as interest rate swaps, total return swaps, credit default swaps, forwards, certain equity options and any other derivative that are generally traded between investment banks and their clients. The investment bank assesses the credit-worthiness of its client (credit risk) and decides what terms it would like to enter into the agreement with its customer.

Before we get into the OTC market, it is important to understand the basics of traditional exchanges. We have all seen the floor of the NYSE and the many people who scurry around with electronic tablets. This is now considered the dying “floor” exchange. Market makers or specialists take orders for specific stocks or products on the basis that under extreme market events they (versus computers) can provide order to utter chaos. The majority of orders now flow through electronic exchanges in sub-second, most often sub-microsecond, time intervals. The electronic exchanges are efficient, fast, and cheap. Billions of shares of equity are traded per day with little or no problems even in the most turbulent of markets. Order prevails on these stock exchanges because the transactions occur on a cash basis. If I want to buy $100,000 worth of IBM, I pay $100,000 in cash. If I do not have the money then I borrow the money from the brokerage firm that I trade through. The brokerage firm limits how much I can borrow and closes out positions if I am not able to meet margin calls. This is the first aspect of leverage.

The true risk in the markets comes in the form of derivatives; contracts that derive their price from some underlying security or risk-factor. Derivatives are used for hedging or speculation and have been very useful for businesses to lock in costs/profits or to limit exposures to market risks. If a farmer is in the business of growing soybeans, he can lock in a price at a certain time before he has even planted the seeds. If a US company buys parts from a company in Europe, that US company can fix the price of those goods by trading forward contracts on the Euro. Airlines can lock in fuel costs by buying futures on crude oil. I think you get the idea.

The tricky part for exchanges handling derivatives is how to account for the leverage being utilized by the customer. If the customer purchases $1,000,000 worth of the S&P 500, how does the exchange know that the customer can afford the price fluctuations on $1M of the S&P 500?

The exchanges handle counterparty risk through two mechanisms:

- Daily mark to market

- Required margin

The daily mark to market can be thought of as a “true-up”. If you are holding a position that moves against you by $5,000 in one day, then at the end of the day $5,000 is taken out of your account. This limits the risk of the exchange to one day of market movements. The margin requirements limit how much you can leverage yourself with a certain product. For the S&P 500, as a speculator, I must have $5,625 in my account for every $56,000 of the S&P 500 that I buy or short through futures. This means that I cannot leverage myself more than about 10 to 1. The two requirements acting together tremendously limit the probability of a large default occurring. The $5,625 protects against a 10% move in the S&P 500 and since the contract is marked to market, the exchange or broker could only lose when the market moves more than +/-10% in 1 day. These requirements change with the volatility of the underlying instruments, but these numbers can be used as an approximate rule of thumb.

Now let us turn out attention to the OTC market with respect to derivatives. The OTC derivatives market started in the 70’s as a way for companies and institutional investors to manage currency and interest rate exposures by entering into contracts with investment banks. The institutions had legitimate hedging problems and the investment banks solved the problem. The issue has come with the size and scope of the OTC market and its embedded risks. The outstanding notional of OTC derivatives contracts stood at $683 Trillion June 2008. Since then, the outstanding notional has fallen to $600 Trillion as of June 2009. The GDP of the United States is approximately $14T and the GDP of the world is $60T. Over 10 times the world GDP is outstanding in OTC derivatives contracts. Over $400T of the outstanding is due to interest rate contracts while $60T is in credit default swap contracts. To put the credit default swap number in perspective, the total international bond market is valued at about $60T.

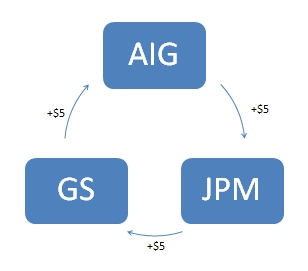

The numbers are difficult to judge because there is a lot of netting in the mix, meaning that contracts theoretically cancel each other out. Goldman Sachs could have sold $50B of CDS protection to AIG but then turned around and bought protection from JP Morgan and JP Morgan could have turned around and bought protection from AIG for a net position of zero. The value of the different contracts offset each other as well. Maybe GS owes JPM $50M on a Ford CDS contract but JPM owes GS $100M on a GM contract so as a net position JPM owes GS $50M. The problem is that theoretical netting is dependent upon the survival of each member of the OTC Ménage à trois. If AIG defaults, then the circle is not complete.

The investment banks must also judge what represents a prudent counterparty risk size for each of its clients. If Goldman Sachs enters into a $50B contract with AIG, how does Goldman Sachs know that AIG has not entered into that same contract with 8 different investment banks? How does Goldman Sachs judge the exposure that AIG has on its books and its ability to pay if the markets move? The answer is that they cannot. Before having to post collateral on OTC contracts, the valuation has to go against the client by a large amount scaled by their credit rating. With a strong AAA credit rating and good negotiations, AIG could have had negative positions of $50M or greater with each of its counterparties before having to post any collateral.

So why are OTC contracts not traded on exchanges? The first and most relevant answer is that each contract needs to be specially designed to address the needs of the client. With respect to interest rate exposures, let’s say that a particular company would like to change its floating rate debt payments to a fixed rate payment. They enter into an interest rate swap in which every floating rate payment is swapped to fixed on the exact dates of the interest payments. This is called cashflow hedging beause the out-flowing cash is matched exactly to the inflowing cash with regards to the date and size of the flow. Likewise, if a client has a large foreign exchange payment due at a specific date in the future then they can enter into a currency forward contract that pays out on the exact date of the cashflow. You could see that these contracts then have many millions of permutations in the way that they are structured. Less of an argument can be made for credit default swaps because 5 year contracts with rolling quarterly maturities have become the de facto standard which should allow larger names to be traded with liquidity on an exchange. Credit Default Swaps could be traded on an exchange with very little difference from all of the equity options being traded on the Chicago Board of Options Exchange. The amusing thing is that interest rate swaps will most likely be the first instrument put on an exchange. Interest rate swaps are no longer very profitable for the banks and the paperwork is overwhelming so they would be happy to offload a good portion of it.

What is truly stopping the move from OTC to the exchanges? Money. Commissions. Spreads. Leverage. Corruption.

Banks make money with every trade made on an OTC contract. There is a bid/ask spread which can be very wide on specific names. In addition, if a client is only trading with one or two counterparties then the bank has a lot of flexibility in fleecing the unknowing client. Who monitors these practices? No one.

And what about transparency? If I am going to buy a large number of shares of Citigroup, do I not have the right to know who has put on a massive short position on their debt via OTC credit default swaps? What about insider trading? Who is to stop someone with insider knowledge from placing their trade in the OTC markets? No one.

Leverage? Where else can you reach leverage levels of 60x or greater? Make a killing off of leverage while things are calm, pay out bonuses, blow up, get bailed out (or restart a new hedge fund), rinse, repeat.

What about corrupt trading practices without regard for traditional corporate governance? What is stopping a hedge fund or institution from buying a massive amount of a company’s debt, a large number of equity shares, and then shorting the stock via OTC equity forward contracts and shorting the debt through OTC credit default swap contracts? The “investor” could have tremendous voting rights as a bondholder, as a shareholder, and have a negative interest in the viability of the company. Thanks for the regulation SEC.